The

Buddha Shakyamuni, at the moment of enlightenment, invoked the earth as

witness, as indicated by the fingers of his right hand, which spread

downward in the bhumisparsha

mudra, the "gesture of touching the earth." As

the

Buddhist Sutras relate, the sun and moon stood still, and all the

creatures of the world came to offer obeisance to the Supreme One who had

broken through the boundaries of egocentric existence. All

Buddhist art

celebrates this supreme moment and leads the viewer toward the Buddha's

experience of selfless and unsurpassed enlightenment. The earliest forms of

Buddhist art were semiabstract: bodhi-trees, wheels, stupas, and even the

Buddha's stylized footprints served as supports for contemplating what was

ultimately beyond words or forms. As the Buddha himself continually taught,

it was not he who was continually revered but the possibility he presented.

"Don't look to me," he said, "but to the enlightened state."

The first anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha are said to have

been drawn on canvas from rays of golden light emanating from his body.

Later Buddhist art pictured the Buddha in numerous manifestations, but

always as an archetype of human potential, never as a historically

identifiable person. All forms of the Buddha, however, are commonly shown

seated on a lotus throne, a symbol of the mind's transcendent nature. As a

lotus rises from the mud to bloom unsullied in open space, so does the mind

rise through the discord of its own experience to blossom in the

boundlessness of unconditional awareness.

Buddhism is not a static doctrine, but a creative expression of the

interdependent nature of all things. It is a means by which we can discover

in the heart of experience, not ourselves, but a luminous and unfolding

mystery. Buddhism envisions the

universe as a net of jewels, each facet of reality reflecting every other

facet. Our calling is not to escape this web of interdependent origination,

but to awaken to our indwelling Buddha nature, to see the world for what it

is, and to become Buddhas in our own right - beings of infinite awareness

and compassion.

"Be a light unto yourself," Buddha Shakyamuni declared at the end of his

life. Become a Buddha, an awakened being, he urged, but never a blind

follower of tradition. Indeed the image of the Buddha, transcending time and

place, centers us in our innermost being.

Shrestha, Romio. Celestial Gallery: New York, 2000.

How are Nepalese copper statues made?

Nepalese statues and sculptures are best known for their unique

small religious figures and ritual paraphernalia for over two

thousand years. These are mainly cast in copper alloy. Nepal draws

influences from the artistic styles of Buddhism and Hinduism, and

therefore the sculptors of the country specialize in making the

icons of both these religions. Over the years, Nepalese sculptures

evolved into their own distinctive iconography. Some

characteristic features of these sculptures that differ from other

pieces are exaggerated physical postures, youthful and sensual

features, languid eyes, wider faces having serene expressions, and

ornate flourishes. The Buddhist deity icons of Nepal have

tremendous demand in countries such as China and Tibet for ritual

purposes in their temples and monasteries.

Nepalese statues and sculptures have a high copper content and

therefore develop a slightly reddish patina on the surface as they

age. However, the most unique feature of Nepalese copper statues

is their decorative detailing. The pieces are heavily gilded and

sometimes inlaid with semi-precious stones. This embellishment

protects them from getting tarnished. The traditional lost-wax

method for casting Nepalese copper statues remains the most

practiced technique in Nepal for many centuries. This process

involves many steps and requires skilled artists.

The first step in lost-wax sculpting is to make a wax replica of

the desired Buddhist deity to be cast in copper. This replica is

created by hand and therefore needs excellent artistic skills

otherwise fine features will be lacking.

Once the wax replica is made, it is then coated with a special

mixture of clay with a brush. This layer of clay is hardened when

left to dry. A small hole is made on the base of the wax mould so

that the wax flows away when it is heated.

At this stage, a hollow mould in the shape of the deity is

obtained.

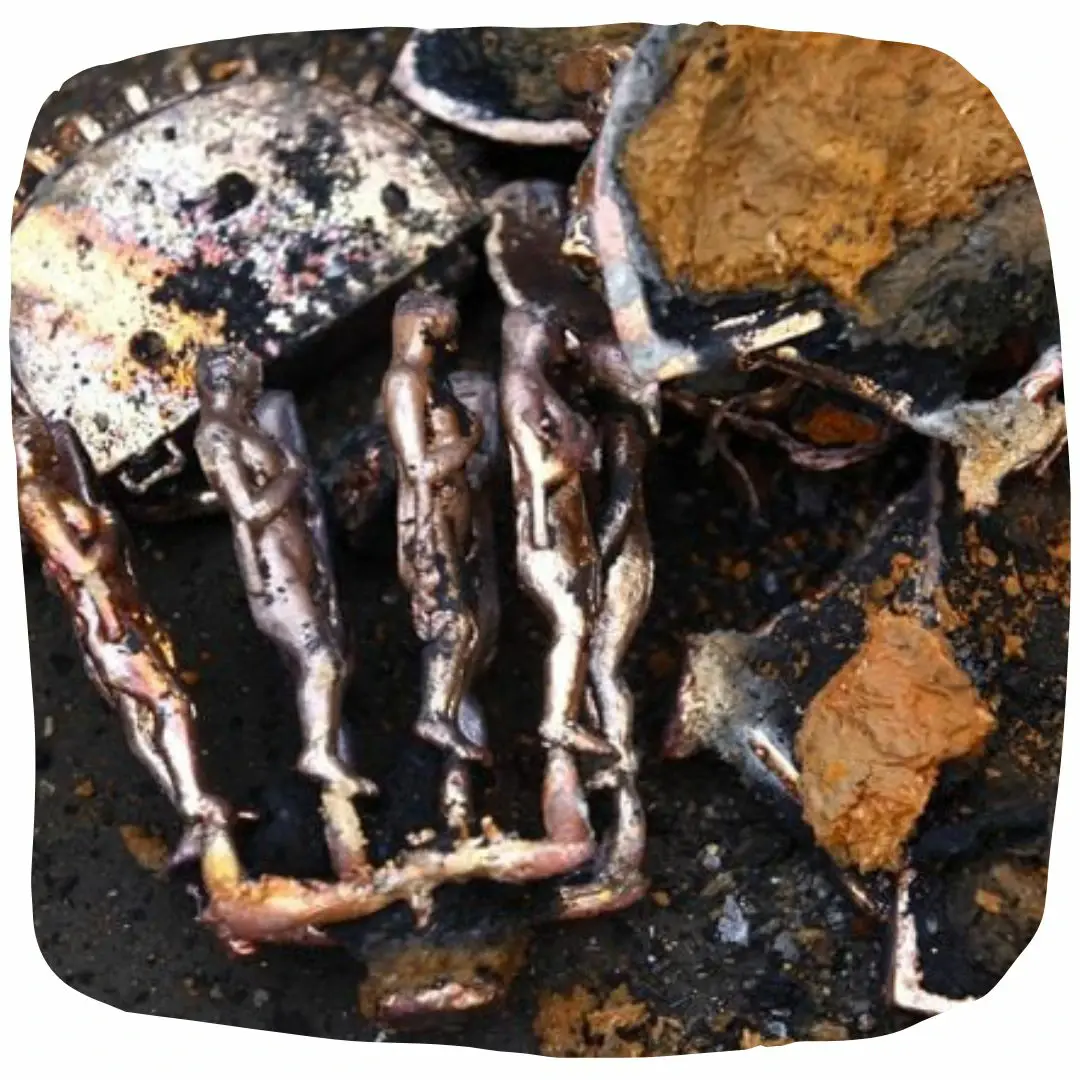

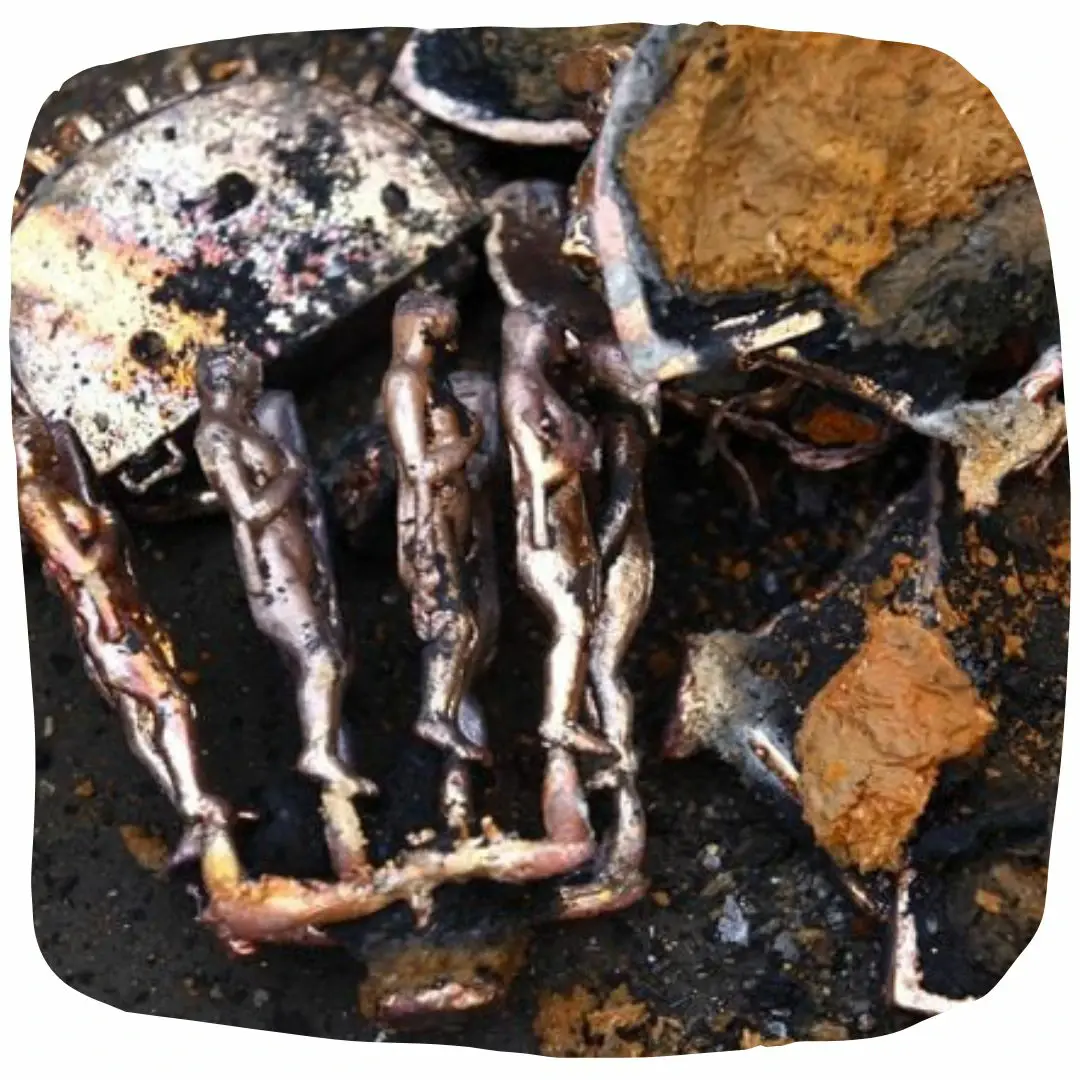

This is the time to pour liquid copper into the hollow mould which

is then allowed to cool and harden inside a container of cold

water. When the liquid metal has hardened, the mould is removed

and the statue within is revealed.

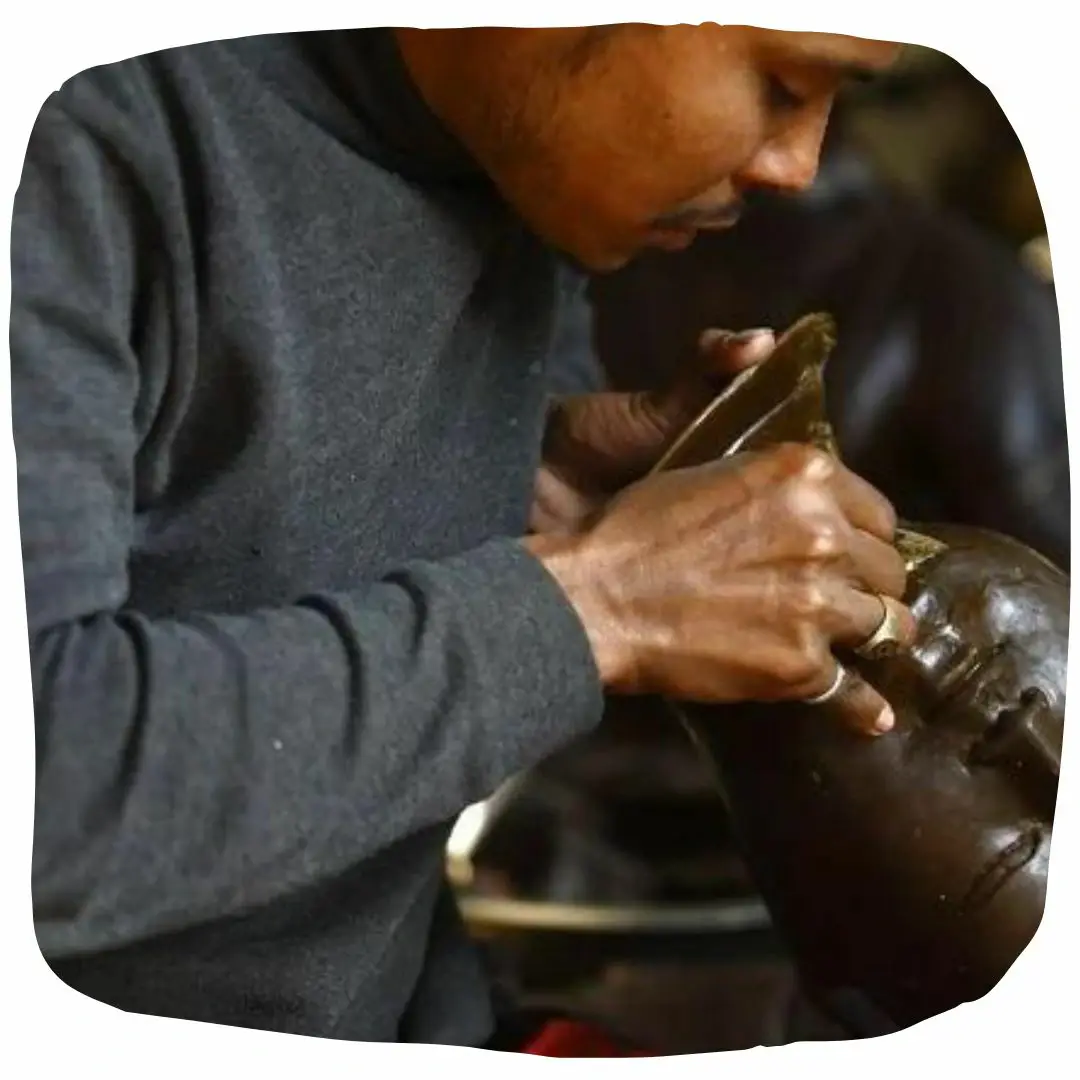

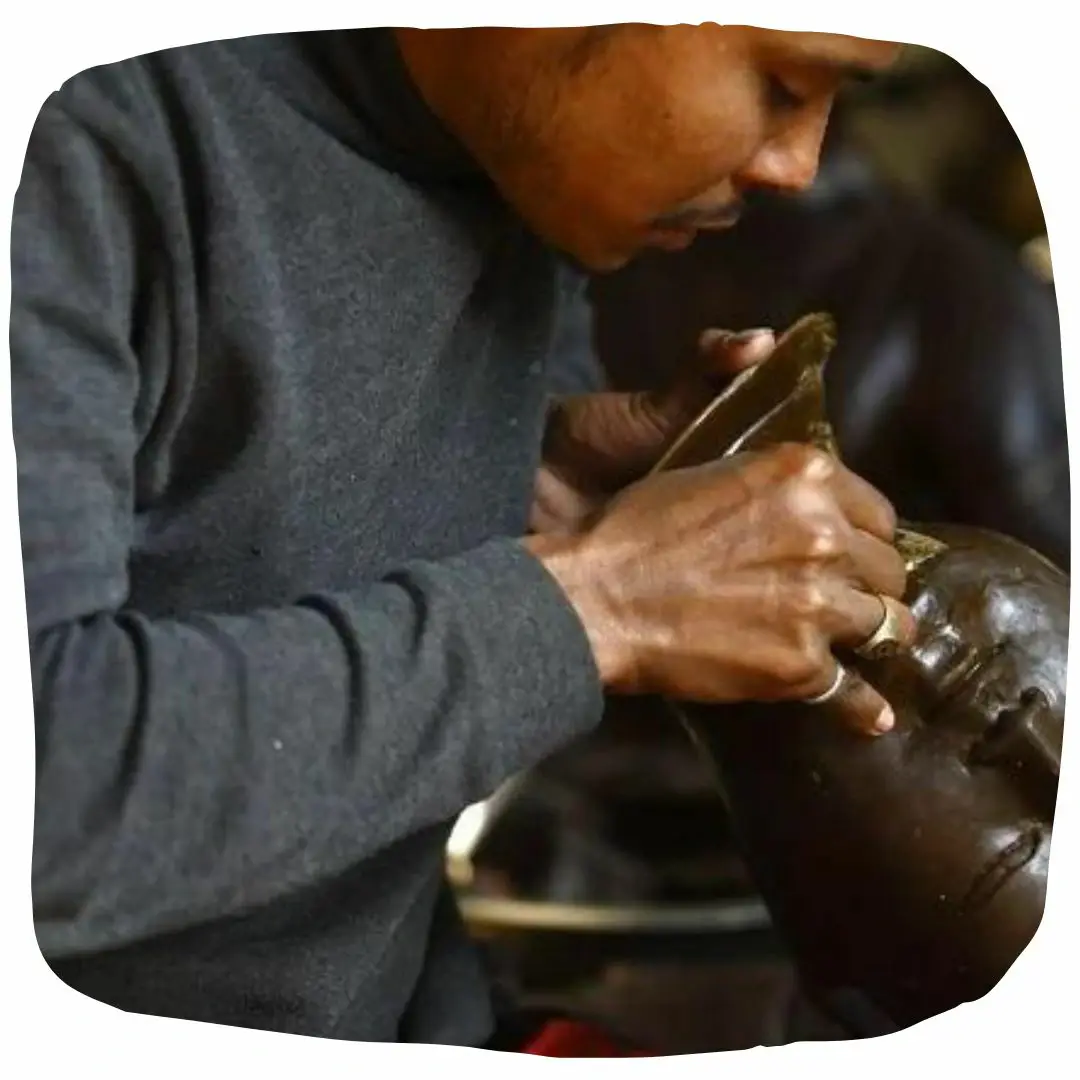

The artist works on the details of the statue using various tools.

It is then polished to get a shiny and lustrous surface.

Now comes the most important part of Nepalese art which is gold

gilding. This is done by the traditional fire gilding method. A

mixture of mercury and 18K gold is applied on the surface of the

statue and heat is applied using a flame torch. The result is that

mercury evaporates along with impurities, leaving a pure 24K gold

finish.

The lost-wax method of sculpting is the most preferred technique

for artists to cast a metallic statue having intricate details.

Since Nepalese copper sculptures require extraneous effort for

giving a majestic look by adding special embellishments, it takes

several weeks to complete one masterpiece. A 24K gold gilded

copper sculpture retains its brilliant luster for many years and

appears as like before. Nepalese sculptures continue to remain one of the finest specimens of the art of the East that have a strong

aesthetic appeal that other sculptures cannot match.